Insight: How Real and Virtual Racers Train Their Mental Capacity

Sportscar365 goes behind the scenes to discover Formula Medicine’s mental training…

Motorsport is, and always has been, a science-driven business. The spirit of competition has pushed the sport to evolve in ways that would have been unthinkable even just a few decades ago. More downforce, more power, more efficiency: modern day racing cars are as complex and fast as they’ve ever been.

But what about the science of human development? Pushing drivers to become better, faster, stronger?

The physical side of that equation has been well understood and applied for decades now. Personal trainers, nutritional plans, physical therapy: all tools commonly used to help racing drivers cope with the high demands of the sport.

What sometimes gets forgotten in that discussion is the mental toll that a high-stress environment such as motorsport takes on drivers. They are in an inherently dangerous situation that often forces them to make split-second decisions. Those decisions can sometimes have enormous ramifications. A driver’s health, livelihood, a race win, a championship - all things that can hang in the balance, depending on the situation.

However, just as the science driving car development never stands still, so too does the sport find a way to train a driver’s mental strength. To discover how, Sportscar365 went behind the scenes with BMW M Motorsport at Formula Medicine to find out how drivers, both in the real world and in esports, can train how to deal with high-pressure situations.

Formula Medicine, based not far from Florence in Italy’s Tuscany region, describes itself as a company offering ‘mental, medical and athletic preparation for top athletes and business people.’ Pay attention and you’ll find its staff working in just about every major motorsports paddock around the globe.

Its list of clientele is as long as it is impressive. The company has worked with many Formula 1 teams and drivers as well as the likes of BMW and Iron Lynx. Its reach extends beyond motorsport and also includes athletes such as tennis star Jannik Sinner.

“Every year we see [about] 350 athletes here,” company founder Riccardo Ceccarelli explains. “Two-hundred, more or less, come from motorsport. Roughly 100 to 150 come from other sports.”

Ceccarelli sat down with Sportscar365 in the middle of a multi-day training camp for BMW’s professional sim racing teams, who were preparing to compete in the Esports World Cup at the end of August.

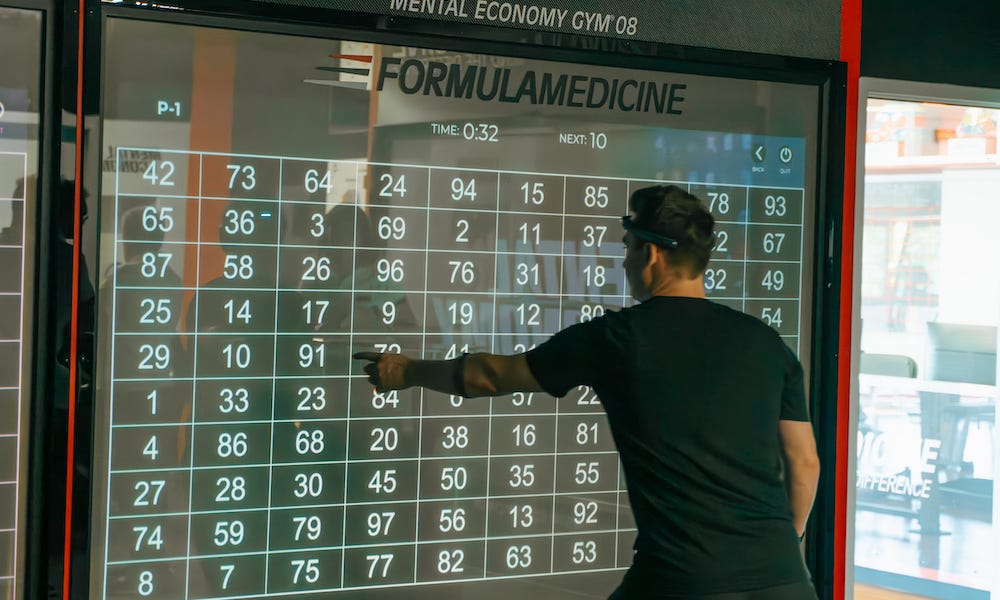

Key to the activities was a program called ‘Mental Economy,’ created by Ceccarelli and Formula Medicine aimed at improving brain efficiency.

“To make it simple, Mental Economy means to have an economical brain,” Ceccarelli, a doctor with 35 years of experience in racing, outlines. “That means: a brain not affected by useless things like overthinking or the fear of making mistakes.

“That means that we are not economical anymore when we are affected by overthinking, which means emotion. When we do the same things without the pressure of the result at every cost, we are more economic.”

The core concept behind Mental Economy was born when Ceccarelli conducted a study comparing the brain function of racing drivers to that of non-athletes.

“We put them inside a functional MRI while they are doing some competitive tests and then we can see how their brain is working,” he says. “The surprise was: they had the same performance, same reaction time. But with the drivers, the activation of the brain was much, much lower compared to the other group.

“So that was the idea. Now we know we have to train the economy of the brain. And that's what started the Mental Economy training.”

Ceccarelli and his team developed a series of exercises, designed at tackling what was described as ‘brain strain,’ thus aiming to have the participants complete said exercises with as little mental exertion as possible.

One key exercise is the so-called ‘Color Test,’ based on the Stroop test that tasks a participant to identify the mismatch of a color and the color said word is displayed in.

With Ceccarelli’s variant, the objective was to complete the test with as low a brain strain as possible while the emphasis was not on getting a perfect score. The goal is clear: the result of the test isn’t crucial - it’s about carrying it out as efficiently as possible.

More notable was a test called the ‘Car Race,’ which pitches three people against each other. The twist: each participant only controlled the speed of the car and that speed was determined by the focus level in your brain. So in order to get a good result, it was encouraged to essentially ignore the race’s many factors and only focus on a single aspect.

As Ceccarelli explained, it’s almost backwards: not caring about every aspect makes you quicker. “The Car Race is fantastic because you are automatically involved,” he says.

“You think about strategy, watching the other cars and analyzing. But the more involved you are in the race, the slower you are. So you need to have the wrong approach, which is also the best approach.

“It's something that we try to transmit to the driver: if you have a high target, you put the pressure [on yourself] and you lose your potential.”

Ceccarelli explained that the exercise program for the sim racers during this training camp was presented with the “same mental approach” as the routines carried out by real-world drivers.

As BMW factory racer and IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship GTP driver Nick Yelloly attests, the training comes with significant upsides.

“I think it will help you mostly for training your extra awareness whilst driving a car,” says Yelloly. “So your mental capacity almost more than anything, and then dealing with lots of information under pressure. Those two things would be the biggest [factors].

“For me, before I did GTs obviously I was in single-seaters and then worked for an F1 team for years. So then when we came to the Hypercar, all the switch changes and button changes were quite natural and it wasn't overloading particularly.

“But for people that were new to that kind of thing, it would have been a big help to be able to train yourself to find the right buttons in the shortest space possible without losing any lap time.”

Yelloly explained that the mental exercises form part of a training regiment that BMW works drivers complete ‘at least a couple of times a year, schedule allowing.’

He adds: “They tend to ramp up the Mental Economy when you're physically tired, because that's what you're going to be in the car. So it's quite a good thing just to swap over, give your body a rest although you're tired and then go back to the physical training.”

Ceccarelli has seen many drivers pass through the Mental Economy program in recent years, including the likes of Dan Harper, Neil Verhagen and Max Hesse when they were still part of the BMW Junior Team.

From his observations, he noted key differences between real and virtual drivers through the training program - the lack of physical feedback tends to sharpen a virtual driver’s mental sensitivity.

“The difference between driving a simulator and driving a real car, it's not the fear of having an accident or being injured, it's not this one,” he says. “Because the professional drivers, they remove this. The difference is that it's technical so there are many things that are technically the same.

“They have to be very precisely coordinated when they drive, find the right line, the setup and then there are so many things which are exactly the same. The mental [strain], fighting with another driver to defend, that is exactly the same.

“The only difference is that sim racers don't have any support from the feeling of the movement of the car. It’s just steering, so they have developed even more brain sensitivity to drive very well. That's why also some top drivers that are not from the generation of the sim when they go on the sim, they're slow.”

According to Ceccarelli, the target of the training for both real and virtual drivers is to reach a certain “perfect cocktail” of competitive spirit and a calm mental state.

“For me, Robert Kubica was the driver closest to perfection,” Ceccarelli says. “He was super competitive. Outside of racing, he was always looking for something to compete in. Bowling, poker, table tennis.

“But he was always starting from zero, yet in six months he was on a high level. He was learning so quickly. And that's because when he was performing he had zero pressure.

“So he was using 99 percent of his skill to learn and then, in competition, to go free as much as possible. So why I say he was the perfect cocktail: huge competitive spirit, which means huge motivation in everything including motorsport, but a very super calm approach so inside the comfort zone.

“That is the perfect cocktail, which is very difficult.”

Referring back to the training, Ceccarelli concludes: “The Car Race is the way that I need to teach you that if you want to win, you have to approach like you don't care.”

Motorsports has always been driven by science. The science behind your mental capacity could very well be the key to unlocking extra performance - whether you race in real life, or behind a simulator.

Photos: BMW